Tariq Saeedi

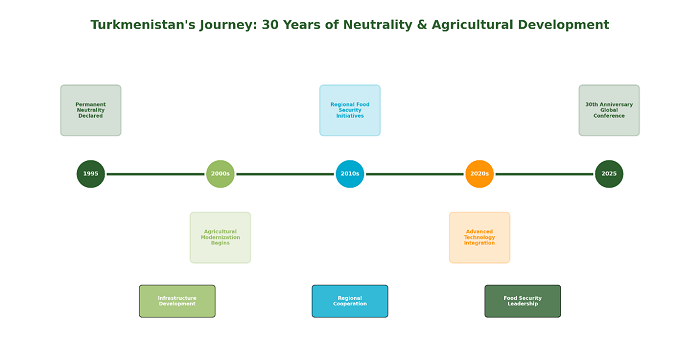

As world leaders gather in Ashgabat this December to commemorate three decades of Turkmenistan’s neutrality, there emerges an unexpected yet profound connection between the philosophy of permanent neutrality and humanity’s most fundamental challenge: feeding the world.

This connection runs deeper than diplomatic ceremony or geopolitical positioning. It touches the very soil from which our sustenance springs.

Beyond Borders: The Universal Nature of Hunger

Hunger recognizes no nationality. A child’s empty stomach in sub-Saharan Africa shares the same ache as one in South Asia or Central America. This simple, terrible truth reveals something essential about our interconnected world: the challenge of food security cannot be solved by nations acting in isolation, nor can it be resolved through the competitive hoarding of agricultural knowledge and technology.

Here lies the first thread connecting neutrality to agriculture.

Just as Turkmenistan’s permanent neutrality represents a commitment to stand outside the divisions that fracture our world, the fight against hunger demands a similar transcendence of narrow self-interest. It requires what we might call “agricultural neutrality”—a recognition that the technologies, techniques, and innovations that increase crop yields and improve nutrition belong, in a moral sense, to all humanity.

The Philosophy of Shared Prosperity

Consider the chain of reasoning that leads us here. — We begin with a simple premise: every person possesses an equal claim to sustenance. From this flows a second truth: those who possess knowledge or technology that can multiply the earth’s bounty bear a responsibility to share it.

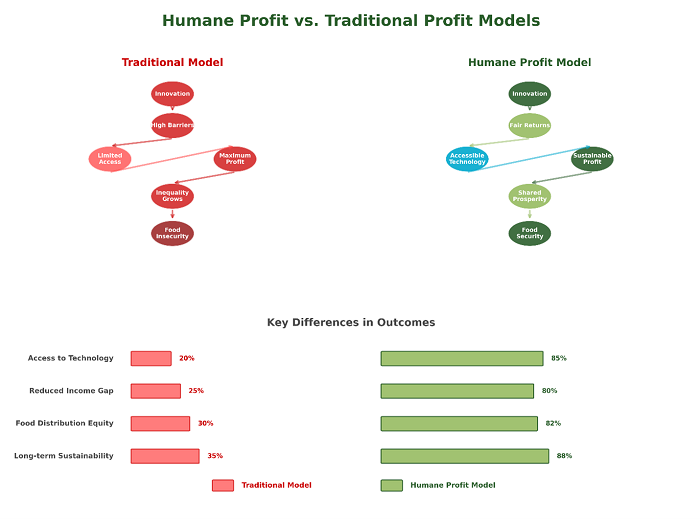

But here’s where the thinking becomes nuanced—this sharing cannot be naive or unsustainable. It must be structured in a way that rewards innovation while ensuring access.

This is what we might call “humane profit“—a model of economic return that acknowledges legitimate rewards for ingenuity and investment, while rejecting the notion that life-saving agricultural advances should be locked behind prohibitive barriers.

It’s profit with a conscience, commerce with a heart.

The farmer who develops drought-resistant seeds deserves prosperity, but not at the cost of millions going hungry because they cannot afford those seeds.

Turkmenistan’s approach to its agricultural development offers a glimpse of this philosophy in practice. The country has invested heavily in modern irrigation systems, greenhouse technologies, and scientific agricultural methods—not merely for export advantage, but as part of a broader commitment to regional food stability. Its neutral stance allows it to serve as a bridge, facilitating agricultural cooperation between nations that might otherwise view each other with suspicion.

The Integrity of Connection

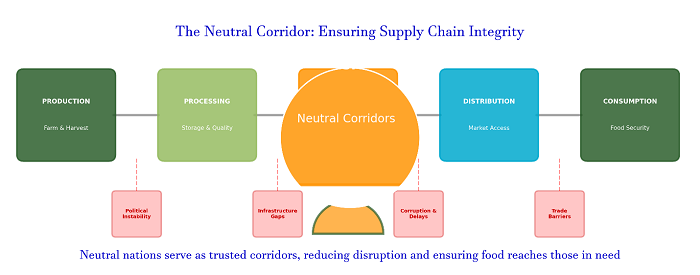

But growing food is only half the equation. The most abundant harvest means nothing if it rots before reaching those who need it. This brings us to the second crucial element: supply chain integrity.

Think of it this way—a supply chain is like a river system. If any tributary is blocked, if any channel is corrupted, the water fails to reach its destination. In our modern food systems, these blockages take many forms: inadequate infrastructure, political interference, inefficient logistics, corruption, or the weaponization of food supplies during conflicts.

A neutral nation, by its very nature, can play a unique role in ensuring these channels remain open.

Switzerland’s humanitarian neutrality during wartime provides a historical parallel—its neutral status allowed it to serve as a conduit for aid and diplomacy when other routes were closed.

Similarly, Turkmenistan’s geographic position and political neutrality position it as a potential corridor for agricultural trade and food security initiatives across Central Asia and beyond.

The country’s investment in transportation infrastructure—railways, highways, and its strategic port facilities on the Caspian Sea—reflects an understanding that neutrality must be practical, not merely philosophical. These are the arteries through which food security flows, connecting regions of surplus with areas of need.

The Holistic Vision

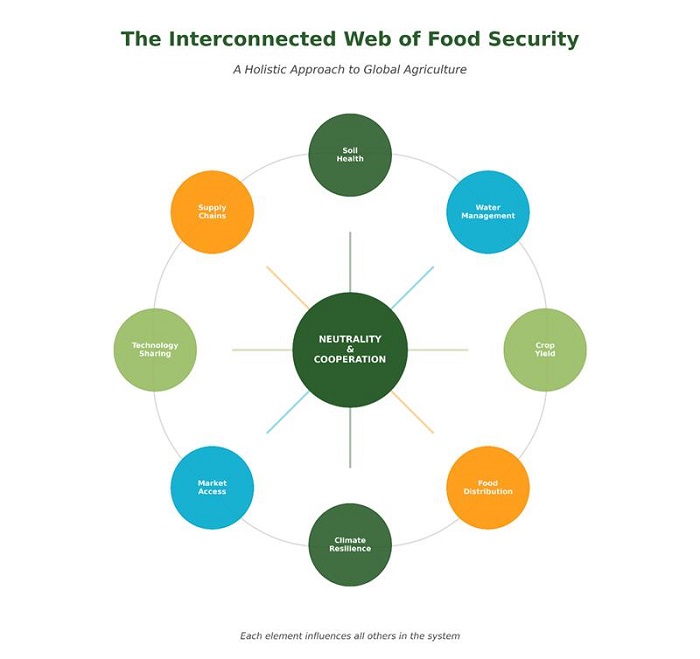

There’s an ancient wisdom that says everything is connected to everything else. — Modern systems theory and ecological science have proven this intuition correct. In agriculture, this interconnection is particularly visible. Soil health affects water quality. Water management impacts crop yields. Crop diversity influences pest resilience. Local food systems connect to global markets. Climate patterns in one region ripple across continents.

This holistic perspective demands a holistic response. It’s not enough to develop a high-yield wheat variety if we ignore the soil depletion it might cause. It’s insufficient to build irrigation systems without considering long-term water sustainability. It’s shortsighted to increase production in one region while ignoring the market access that would allow that production to benefit those most in need.

Turkmenistan’s experience over thirty years of neutrality demonstrates this integrated thinking.

The country has pursued agricultural modernization alongside environmental protection, increased production capacity alongside regional cooperation, and technological advancement alongside traditional sustainable practices. The neutrality framework has provided the stability necessary for long-term agricultural planning—something often missing in regions plagued by conflict or political instability.

A Model Worth Studying

As the international community gathers in Ashgabat this December, there’s an opportunity to examine how the principles of neutrality might be applied more broadly to global food security challenges.

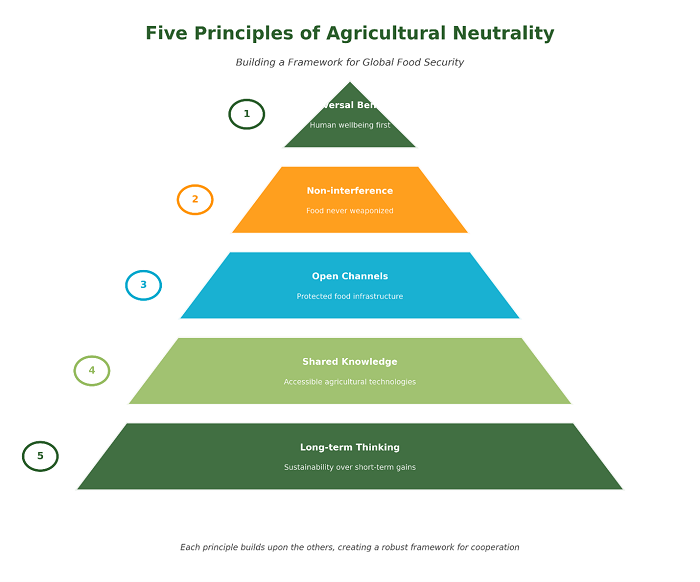

This doesn’t mean every nation should or could adopt permanent neutrality as Turkmenistan has. Rather, it suggests that certain neutral principles could guide international agricultural cooperation:

- The principle of universal benefit: Agricultural innovations should be developed and shared with the understanding that their ultimate purpose is human wellbeing, not merely profit maximization or competitive advantage.

- The principle of non-interference: Food supplies should never be weaponized. Nations should commit to keeping agricultural trade and food aid channels open even during political disputes.

- The principle of open channels: Infrastructure for food transportation and storage should be treated as neutral territory, protected even in times of conflict, much as medical facilities receive special protection under international law.

- The principle of shared knowledge: While respecting intellectual property rights and the need for sustainable business models, the global community should work toward making essential agricultural technologies accessible to regions facing acute food insecurity.

- The principle of long-term thinking: Agricultural policies should prioritize long-term sustainability and soil health over short-term exploitation, recognizing that today’s overproduction through destructive methods becomes tomorrow’s famine.

The Practical Path Forward

These principles aren’t merely philosophical abstractions. They point toward concrete actions: international seed banks that preserve crop diversity; technology transfer agreements that make drought-resistant crops available to vulnerable regions; international investment in agricultural infrastructure in food-insecure areas; training programs that spread advanced farming techniques; and trade agreements that reduce barriers to agricultural products from developing nations.

Turkmenistan’s neutral status has allowed it to engage constructively with diverse partners—from East to West, from developed to developing nations—without the complications that alliances and rivalries create. This flexibility has practical benefits for agricultural cooperation, allowing for the kind of multidirectional knowledge sharing and resource exchange that food security demands.

The Harvest We Might Reap

Thirty years is a significant milestone—long enough to demonstrate that neutrality isn’t merely a diplomatic posture but a workable framework for national development and international engagement.

As climate change intensifies agricultural challenges, as population growth increases demand for food, and as geopolitical tensions threaten to disrupt supply chains, the need for neutral spaces and neutral principles in global food systems becomes more urgent.

The December conference in Ashgabat offers more than a celebration of Turkmenistan’s journey. It presents an invitation to consider how the philosophy underlying that neutrality—the commitment to peace, cooperation, and mutual benefit—might address humanity’s most fundamental need: the need to eat.

If we can think beyond national advantage to collective survival, if we can structure our agricultural systems around humane profit rather than maximum extraction, if we can treat the infrastructure of food security as sacred and neutral ground, then perhaps we can harvest something more valuable than any single crop—the peace of mind that comes from knowing no child need go hungry in a world of plenty.

This is the promise that neutrality, properly understood and applied, holds for global food security. It’s a harvest worth working toward, and a model worth studying as we face the agricultural challenges of the decades ahead.

The gathering in Ashgabat this December will celebrate thirty years of one nation’s commitment to neutrality. Perhaps it can also plant seeds – quite literally – for a more neutral, more cooperative, more humane approach to feeding the world. /// nCa, 18 November 2025