Tariq Saeedi

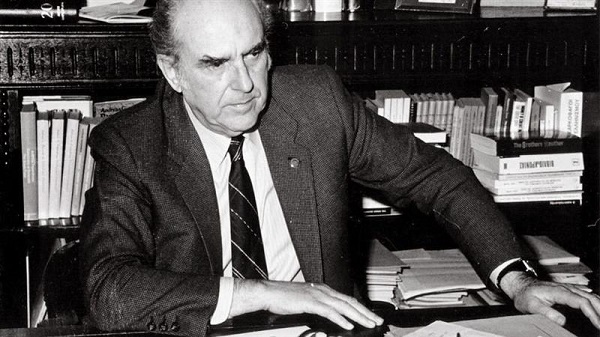

Andreas Papandreou, the charismatic socialist leader who twice served as Greece’s Prime Minister in the 1980s and 1990s, once declared that he did not want to turn his country into a “nation of waiters.” It was a bold vision, born from a deep-seated desire to elevate Greece beyond the sun-soaked beaches and tavernas that drew tourists in droves.

The story of Papandreou and his Greece is a story of great significance for everyone today, including Central Asia.

Papandreou dreamed of a modern, industrialized nation where Greeks produced, innovated, and thrived on their own terms, free from the whims of foreign capital and seasonal visitors.

As the founder of the Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK), he rode into power in 1981 on a wave of popular support, promising to redistribute wealth, empower the working class, and build a self-sufficient economy. For a time, it seemed like he was succeeding. But as history unfolded, his well-intentioned reforms sowed the seeds of fiscal ruin, turning a story of hope into one of tragedy.

What went wrong? And what can today’s leaders learn from this cautionary tale?

Papandreou’s approach was quintessentially socialist, infused with a passion for state-led transformation. Coming from an academic background in economics—having studied at Harvard and taught at Berkeley—he viewed Greece’s post-war economy as overly dependent on services like tourism and shipping, which he saw as precarious and unequal.

To counter this, he launched an ambitious program of nationalizations, public sector expansion, and support for local industries.

In 1983, his government took over hundreds of struggling private companies, dubbing them “problematics,” and placed them under state control through the Industrial Reconstruction Organisation. The goal was noble: prevent layoffs, keep production local, and foster a domestic industrial base. He also poured resources into agricultural cooperatives, especially empowering women in rural areas, and boosted small-to-medium enterprises (SMEs) with subsidies and protections against multinational giants.

On the surface, these measures worked wonders in the short term.

Public sector hiring exploded, salaries and pensions rose sharply— the minimum wage jumped 32% in 1982 alone—and a burgeoning middle class emerged with newfound purchasing power.

Greeks felt empowered; the welfare state expanded, including the creation of a national health system that remains a cornerstone today. Papandreou’s rhetoric of anti-imperialism and economic sovereignty resonated deeply, uniting a nation still healing from decades of dictatorship and foreign influence. For many, it was a golden era of social mobility and national pride.

Yet, beneath the veneer of progress, cracks were forming. The policies, while popular, failed to address the harsh realities of global competition and economic efficiency.

Nationalized industries didn’t magically become productive; instead, they often became vehicles for political patronage, where jobs were handed out to loyalists rather than based on merit.

Productivity stagnated, and many firms operated at a loss, draining public coffers. The massive public sector expansion fueled a culture of entitlement, where wages outpaced output, leading to a loss of competitiveness. Multinationals like Goodyear and Pirelli fled, taking jobs and expertise with them. Agriculture, once a surplus sector, flipped to a deficit by 1986 as inflated labor costs made farming unviable without cheap workers.

The economic indicators told a grim story. Greece entered a period of stagflation: growth averaged a paltry 0.7% annually through the 1980s, while inflation raged at 19.5%. To finance it all, Papandreou turned to foreign borrowing, tripling the debt-to-GDP ratio from 22.7% in 1980 to 72.5% by 1990.

This wasn’t just numbers on a ledger; it was a ticking time bomb. His vision of state-supported SMEs clashed with the emerging forces of globalization, where efficiency and innovation trumped protectionism.

In essence, Papandreou’s good intentions—rooted in a genuine desire to uplift the masses—collided with economic fundamentals. He prioritized redistribution over sustainable growth, assuming the state could indefinitely subsidize prosperity without consequences.

This tragedy wasn’t inevitable, but it stemmed from a few key missteps. — First, there was an overreliance on debt-financed spending without corresponding reforms to boost productivity. Papandreou’s administration expanded demand through public largesse but neglected supply-side improvements like education, infrastructure, or R&D that could have made Greek industries truly competitive.

Second, the policies fostered dependency: by shielding local businesses from competition, they inadvertently weakened them, much like overprotecting a child stunts their independence.

Third, political expediency played a role; the short-term popularity of handouts masked long-term risks, a classic pitfall in democracies where leaders face reelection pressures. Papandreou, supported by a nation eager for change after years of conservative rule, had the mandate to push bold ideas—but boldness without pragmatism led to imbalance.

Fast-forward to 2026, and Greece’s economy paints a stark contrast, often hailed as an “unlikely success story.” After the devastating debt crisis of the 2010s—ironically exacerbated by the imbalances Papandreou helped create—the country has clawed its way back through painful reforms.

GDP is set to grow 2.2-2.4% this year, outpacing the Eurozone average, fueled by tourism (ironically), private investment, and EU recovery funds. Unemployment has dipped to 8.2-8.6%, the lowest since 2009, and the debt-to-GDP ratio is plummeting toward 138%, with early loan repayments underway. Credit ratings are stable at investment grade, thanks to fiscal discipline like primary surpluses (4.8% of GDP in 2024) and structural changes: slashing red tape, modernizing labor laws, and digitizing government services.

Papandreou gets little credit for this turnaround; in fact, his legacy is often blamed for the mess that necessitated it. While he’s praised for building the welfare state and empowering the lower-middle class, economists point to his era as the origin of Greece’s debt addiction and bloated public sector.

Today’s leaders, under a more centrist approach, have embraced fiscal prudence and foreign investment— a deliberate pivot away from state-led excess. Tourism, once derided by Papandreou, now thrives alongside green energy and digital initiatives, showing that diversification doesn’t mean abandoning strengths but building on them sustainably.

So, what lessons can politicians and decision-makers draw today? — First, balance idealism with realism: social justice is vital, but it must be funded by genuine growth, not endless borrowing. Leaders like Papandreou teach us that empowering people short-term can erode foundations if it ignores competitiveness—think of modern debates over universal basic income or green transitions, where subsidies must pair with innovation incentives.

Second, beware the allure of patronage; policies should foster self-reliance, not dependency, to avoid turning economic aid into political tools.

Third, embrace adaptability: in a globalized world, protectionism can backfire, as seen in ongoing trade wars or Brexit fallout. Finally, long-term thinking is key—electoral cycles tempt quick wins, but true leadership measures success in decades, not terms. For emerging economies or even established ones facing inequality, Papandreou’s story warns against consuming tomorrow’s wealth today.

In the end, Papandreou’s own words capture the heartbreak: by the close of his first term, he lamented that “we consume more than we produce.” It was an admission of defeat, from a leader who started with such promise. His tale reminds us that even the best intentions, backed by national fervor, can lead to ruin if not tempered by economic wisdom.

Greece’s recovery today offers hope, but it’s a hard-won reminder that progress demands vigilance. /// nCa, 5 February 2026