Tariq Saeedi

Introduction

When I first learned about President Trump’s Board of Peace (BoP), I expected something profound and of lasting value from someone of his intellectual stature.

What I discovered instead was a deeply troubling document that raises more questions than it answers. — The BoP charter appears to be a hastily constructed framework that diverges dramatically from its UN-authorized mandate, lacks basic governance mechanisms, and positions itself as either a rival to or replacement for the United Nations Security Council without the institutional safeguards that make such bodies functional.

The Gaza Disappearing Act: A Charter Untethered from Its Origins

Perhaps the most glaring issue with the BoP is the complete disconnect between what was authorized by the UN Security Council and what has been created.

UN Security Council Resolution 2803, adopted on November 17, 2025, specifically welcomed the establishment of the Board of Peace “as a transitional administration with international legal personality that will set the framework, and coordinate funding, for the redevelopment of Gaza” (emphasis mine).

The resolution made clear this was to operate “until such time as the Palestinian Authority (PA) has satisfactorily completed its reform program” and could “securely and effectively take back control of Gaza.”

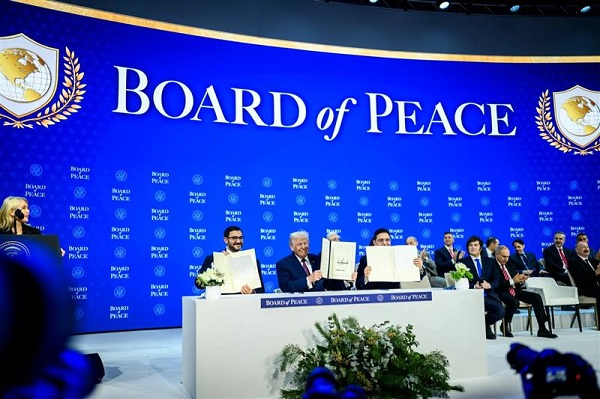

The mandate was clear: Gaza reconstruction, with an implicit end date tied to PA reforms and the 2027 timeframe for the International Stabilization Force. Yet when I examined the actual charter of the Board of Peace signed in Davos on January 22, 2026, I was astonished to find that Gaza is not mentioned even once. Not a single reference.

Instead, the charter describes the BoP as “an international organization that seeks to promote stability, restore dependable and lawful governance, and secure enduring peace in areas affected or threatened by conflict” – a mandate so broad it could justify intervention anywhere on Earth.

Trump himself confirmed this mission creep when he stated at Davos: “I think we can spread out to other things as we succeed with Gaza. We’re going to be very successful in Gaza. It’s going to be a great thing to watch and we can do other things. We can do numerous other things. Once this board is completely formed, we can do pretty much whatever we want to do” (emphasis mine).

This is not the organization the UN Security Council authorized. This is something else entirely.

No Expiration Date: A Permanent Institution by Design

Compounding this problem is the complete absence of any sunset clause or expiration date in the BoP charter.

Resolution 2803 authorized activities until the PA completed reforms and could resume control of Gaza, with the International Stabilization Force explicitly temporary. The resolution clearly envisioned a transitional mechanism with a defined endpoint.

The BoP charter, by contrast, establishes what appears to be a permanent international organization with no provisions for dissolution or transfer of authority. There is no timeline, no conditions for termination, no criteria by which the Board would declare its mission accomplished and cease to exist. — This transforms what was supposed to be a temporary Gaza reconstruction oversight body into an indefinite global entity chaired by a former U.S. president.

The Succession Crisis: No Plan for Leadership Continuity

For an organization that aspires to play a major role in international peace and security, the BoP has a shockingly inadequate succession mechanism. According to the charter, Trump can only be replaced as chairman through “voluntary resignation or as a result of incapacity, as determined by a unanimous vote of the Executive Board.”

Think about the implications of this:

- No natural succession: There is no provision for what happens when Trump’s term as chairman naturally ends, because the charter doesn’t contemplate his term ending at all. Trump has indicated he wants to remain chairman for life, independent of his role as U.S. president.

- Incapacity requires unanimity: If Trump becomes incapacitated, all seven members of the Executive Board must unanimously agree on this determination. In practice, this means any single member loyal to Trump could block a succession, leaving the organization leaderless or under the control of an incapacitated chairman.

- No designated successor: Even if the Executive Board unanimously determines incapacity, the charter provides no mechanism for selecting a new chairman. Who decides? How is the selection made? What qualifications are required? The charter is silent.

- No removal for cause: There is no provision for removing a chairman who, while not technically incapacitated, proves incompetent, corrupt, or acts against the organization’s stated purposes. The only path is voluntary resignation – essentially, Trump would have to fire himself.

Compare this to the UN Security Council, where the presidency rotates monthly among member states according to established rules. Or consider virtually any democratic institution, which has clear succession mechanisms, term limits, and procedures for removal. The BoP has none of this.

From someone of Trump’s intellectual stature, I expected a more thoughtful approach to institutional continuity.

Executive Board Selection: An Opaque Process

The composition of the Executive Board raises equally troubling questions. The seven members announced on January 17, 2026, are:

- Donald Trump (Chairman)

- Marco Rubio (U.S. Secretary of State)

- Jared Kushner (Trump’s son-in-law)

- Steve Witkoff (U.S. Special Envoy to the Middle East)

- Tony Blair (Former UK Prime Minister)

- Ajay Banga (President of the World Bank Group)

- Marc Rowan (CEO of Apollo Global Management)

What are the criteria for Executive Board membership? The charter doesn’t say. How were these individuals selected? The charter doesn’t say. What qualifications do they need? The charter doesn’t say. If one of them resigns or dies, how is a replacement chosen? The charter doesn’t say.

This is not a minor oversight. The Executive Board makes decisions by majority vote (subject to Trump’s veto), meaning these seven individuals have enormous power over what could become a global peace and security mechanism. Yet there is no transparency about how they were chosen, no clear process for replacing them, and no stated criteria for membership beyond the chairman’s discretion.

The nepotistic inclusion of Jared Kushner, Trump’s son-in-law, is particularly problematic. While Kushner has experience with Middle East policy, his appointment raises obvious questions about conflicts of interest and whether the Executive Board is truly an independent international body or a family enterprise.

Member State Selection: Pay-to-Play Diplomacy

The criteria for Board of Peace membership among states is equally concerning. According to the charter, “membership in the Board of Peace is limited to States invited to participate by the Chairman.” Not elected by the member states. Not recommended by the UN. Simply invited by Trump.

Member states serve three-year terms – except for those that “contribute more than USD $1,000,000,000 in cash funds to the Board of Peace within the first year of the charter’s entry into force,” who receive permanent membership. This is unprecedented in international organizations. It’s a literal pay-to-play arrangement where wealthy nations can buy permanent seats at the table.

The UN Security Council, by contrast, has five permanent members established by the UN Charter based on their role as victorious powers in World War II, and ten rotating members elected by the UN General Assembly with attention to equitable geographical distribution and contributions to international peace and security. While far from perfect, this system at least attempts to balance power and ensure broad representation.

The BoP simply sells permanent membership to the highest bidder. And all membership – permanent or temporary – ultimately depends on a personal invitation from Donald Trump. This is not an international organization; it’s a club where the founder picks the members.

An Indescribable Entity: Parallel UN or Rogue Actor?

Perhaps the most fundamental question is: What exactly is the Board of Peace?

The charter describes it as “an international organization” with “international legal personality,” but this raises more questions than it answers. Is it:

- A UN subsidiary body? No. Resolution 2803 welcomed its establishment but did not create it as a subsidiary organ. The charter makes no mention of reporting to or coordinating with the UN beyond vague references to working “in conjunction” with it.

- A regional organization under Chapter VIII of the UN Charter? No. It’s not regional in scope – the charter gives it global reach.

- A coalition of the willing? Perhaps, but unlike previous coalitions (like the Multinational Force in Iraq), it claims permanent institutional status and broad governance authority.

- A parallel to the UN Security Council? This seems to be the intent, but without the legitimacy, accountability mechanisms, or international consensus that underpin the UNSC.

Trump himself has been contradictory, sometimes saying the BoP will work “alongside” the UN, other times suggesting it “might” replace it. The charter provides no clarity on this fundamental question of the organization’s nature and place in the international order.

The Question of Military Intervention: Who Authorizes Force?

This ambiguity becomes acutely dangerous when considering the use of force. Resolution 2803 authorized the Board of Peace to establish an International Stabilization Force in Gaza and to “use all necessary measures to carry out its mandate.”

In UN terminology, “all necessary measures” is well-understood code for authorization to use military force.

But that authorization was specifically for Gaza, under a Chapter VII mandate from the Security Council. What happens when the BoP – which now claims global scope – decides military intervention is needed somewhere else?

Can it authorize force on its own authority?

The charter suggests it can establish subsidiary entities and take actions “as may be approved in accordance with this Charter, including the development and dissemination of best practices.” It authorizes the chairman to “adopt resolutions or other directives” on behalf of the BoP. — Does this include resolutions authorizing military force?

Under international law, only the UN Security Council has the authority to authorize the use of force (except in cases of self-defense under Article 51 of the UN Charter). The BoP charter seems to assume it inherits this authority for any conflict zone it chooses to engage with, but provides no mechanism for ensuring such actions comply with international law or have proper multilateral authorization.

If the BoP authorizes military intervention somewhere, is that legal? Who determines legality? — The chairman, who is “the final authority regarding the meaning, interpretation, and application of this Charter”? This is a recipe for unilateral military action dressed up in the language of multilateralism.

Comparative Analysis: BoP Charter vs. UN Charter (Chapter V – Security Council)

To truly understand how unusual the Board of Peace is, it’s instructive to compare its charter with the relevant provisions of the UN Charter governing the Security Council.

Purposes and Objectives

UN Charter (Article 24): “In order to ensure prompt and effective action by the United Nations, its Members confer on the Security Council primary responsibility for the maintenance of international peace and security, and agree that in carrying out its duties under this responsibility the Security Council acts on their behalf.”

The Security Council’s authority derives from UN member states, who collectively agree that it acts on their behalf. Its purpose is clearly defined: maintenance of international peace and security.

BoP Charter (Article 1): “The Board of Peace is an international organization that seeks to promote stability, restore dependable and lawful governance, and secure enduring peace in areas affected or threatened by conflict.”

The BoP’s authority derives from… the charter itself? The member states who sign it? Trump, who invites the members? The purposes are similarly broad but lack the clear mandate and source of authority that characterizes the UNSC.

Commonality: Both organizations aim to promote peace and security.

Difference: The UNSC has clear authority delegated by all UN member states (193 countries) through a charter ratified by their governments. The BoP has whatever authority its approximately 25 member states choose to give it, with membership contingent on personal invitation and, for permanent membership, a billion-dollar payment.

Composition and Membership

UN Charter (Article 23): “The Security Council shall consist of fifteen Members of the United Nations. The Republic of China, France, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, and the United States of America shall be permanent members of the Security Council. The General Assembly shall elect ten other Members of the United Nations to be non-permanent members of the Security Council, due regard being specially paid, in the first instance to the contribution of Members of the United Nations to the maintenance of international peace and security and to the other purposes of the Organization, and also to equitable geographical distribution.”

Five permanent members are designated in the charter. Ten rotating members are elected by the General Assembly (representing 193 countries) with attention to contribution to peace/security and geographical distribution.

BoP Charter (Articles 2-3): “Membership in the Board of Peace is limited to States invited to participate by the Chairman… [Members] shall serve a term of no more than three years… [except] the three-year membership term shall not apply to member states that contribute more than USD $1,000,000,000 in cash funds to the Board of Peace within the first year.”

All members are personally invited by the chairman. Permanent membership is available for purchase at $1 billion. No attention to geographical distribution or equitable representation.

Commonality: Both have categories of permanent and non-permanent members.

Difference: UNSC permanent membership is based on historical/political considerations enshrined in the charter; rotating membership is elected democratically with attention to representation. BoP permanent membership is for sale; temporary membership depends on a personal invitation from one individual.

Decision-Making and Voting

UN Charter (Article 27): “Each member of the Security Council shall have one vote. Decisions of the Security Council on procedural matters shall be made by an affirmative vote of nine members. Decisions of the Security Council on all other matters shall be made by an affirmative vote of nine members including the concurring votes of the permanent members.”

Clear voting procedures. Each member has one vote. Substantive decisions require nine affirmative votes including all five permanent members (the famous veto power). The veto is shared among five nations.

BoP Charter (Article 4): “The Board of Peace will convene voting meetings at least annually… Each member state shall have one vote. Decisions shall be made by a majority of member states present and voting… Decisions shall be subject to the approval of the Chairman, who may also cast a vote in his capacity as inaugural representative of the United States… The Chairman may, at any time, veto any decision of the Board of Peace or, acting on behalf of the Board of Peace, adopt resolutions or other directives.”

Each member state has one vote. Decisions require a majority. BUT: All decisions are subject to approval by the chairman, who has absolute veto power AND can unilaterally adopt resolutions on behalf of the entire Board.

Commonality: Both systems include veto power.

Difference: The UNSC distributes veto power among five nations, requiring consensus among them. The BoP concentrates absolute veto power in one individual, who can also act unilaterally on behalf of the organization. This is not collective security; it’s autocracy.

Accountability and Oversight

UN Charter (Article 24.3 and 15): “The Security Council shall submit annual and, when necessary, special reports to the General Assembly for its consideration… The General Assembly shall receive and consider annual and special reports from the Security Council.”

The Security Council must report to the General Assembly, which represents all UN member states. There is an oversight mechanism.

BoP Charter: No provision for reporting to any higher authority. No oversight mechanism. The chairman is “the final authority regarding the meaning, interpretation, and application of this Charter.” There is no appeal, no oversight body, no accountability structure.

Commonality: None.

Difference: The UNSC, despite having enormous power, must report to the broader UN membership. The BoP is accountable to no one except its own chairman.

Scope of Authority

UN Charter (Articles 24, 25, and 39-51 – Chapters VI and VII): The Security Council can investigate disputes, recommend peaceful settlement, determine threats to peace, and authorize measures ranging from sanctions to military force. This authority is explicitly granted and limited by the Charter.

BoP Charter (Article 1 and 6): The BoP can “undertake such peace-building functions… as may be approved in accordance with this Charter” and can “establish subsidiary entities as deemed appropriate by the Chairman.” The scope is essentially unlimited, bounded only by what the chairman approves.

Commonality: Both can address threats to peace and security.

Difference: The UNSC’s powers are defined and constrained by the Charter. The BoP’s powers are whatever the chairman decides they should be.

Duration and Termination

UN Charter: The United Nations and its Security Council are established as permanent institutions for “succeeding generations” with no expiration date. However, the Charter can be amended by a two-thirds vote of the General Assembly including all permanent UNSC members, and the UN could theoretically be dissolved by member states.

BoP Charter: Established with no expiration date and no dissolution mechanism. The Charter can be amended by proposal from the Executive Board or one-third of member states, with approval requiring… well, the charter doesn’t actually specify the voting threshold for amendments, only that they must be circulated 30 days in advance.

Commonality: Both are intended as long-term institutions.

Difference: The UN was established by the collective will of nations emerging from World War II with clear amendment and accountability procedures. The BoP was established by Trump’s invitation with unclear amendment procedures and no accountability.

Summary of Key Deficiencies

After examining the Board of Peace charter in detail and comparing it to the established framework of the UN Security Council, I find the following critical deficiencies:

- Mandate Drift: Authorized for Gaza reconstruction, the BoP charter claims global scope without geographical or temporal limits.

- No Sunset Clause: Unlike the temporary transitional authority envisioned in Resolution 2803, the BoP has no expiration date or conditions for dissolution.

- Succession Crisis: No clear mechanism for replacing the chairman, no term limits, no provisions for natural succession or removal for cause.

- Opaque Selection: No stated criteria for Executive Board membership or process for filling vacancies.

- Pay-to-Play Membership: Permanent membership available for $1 billion, temporary membership by personal invitation only.

- Concentrated Power: Absolute veto and unilateral decision-making authority in a single individual, with no checks or balances.

- No Accountability: No reporting requirements, no oversight body, no appeal mechanism.

- Ambiguous Legal Status: Unclear whether it’s a UN body, regional organization, coalition, or something else entirely.

- Unlimited Scope: Can theoretically intervene anywhere the chairman decides, with no clear legal basis.

- Force Authorization Ambiguity: Unclear whether and how the BoP can authorize military intervention beyond Gaza.

Conclusion

I looked at the Board of Peace with genuine curiosity. Given Trump’s intellectual stature and his stated ambition to create something of lasting value, I expected to find a well-thought-out framework for international cooperation on peace and security. What I found instead deeply disappointed me.

The BoP charter reads like a first draft that was never subjected to serious legal review or compared against international norms.

It takes an organization authorized for temporary Gaza reconstruction and transforms it into an indefinite global entity with no sunset clause. It concentrates unprecedented power in a single individual with no meaningful checks, balances, or succession planning. It sells permanent membership to the highest bidder while giving the chairman absolute veto power and unilateral decision-making authority.

Most troublingly, it’s unclear what the BoP actually is. Is it a parallel United Nations? A replacement for the Security Council? A coalition of willing states? A private club? The charter doesn’t say, and Trump’s own statements have been contradictory.

When I compare the BoP charter to Chapter V of the UN Charter, the differences are stark. The UN Security Council, for all its flaws, has clear authority delegated by member states, defined powers and limits, shared veto power among five nations, reporting requirements to the General Assembly, and established procedures for operation.

On the other hand, the BoP has personal invitations, pay-to-play membership, absolute power in one individual, no accountability, and unlimited scope.

This is not the work of deep strategic thinking. This is not a framework built to last. This is an improvised structure that gives Trump personal control over what claims to be an international organization, without the institutional safeguards that make international organizations function.

From someone of Trump’s intellectual stature, I expected better. I expected profound. I expected lasting value. What I found is a charter that appears to have been drafted hastily, without careful thought to succession, accountability, legal status, or long-term viability.

Many aspects of this Board of Peace are clearly not thought out – and that may be the kindest thing I can say about it.

The international community’s response speaks volumes: Major European allies including France, Germany, and the UK declined to join. Only about 25 of 60 invited countries signed the charter. France explicitly warned that it “raises serious questions, in particular with respect to the principles and structure of the United Nations, which cannot be called into question.”

They were right to be concerned. The Board of Peace, as currently constituted, is not a thoughtful contribution to international peace and security architecture. It’s a poorly designed vehicle for concentrating power in one individual’s hands, untethered from the very UN mandate that was supposed to authorize it.

This is not what the world needs, and it’s not what I expected from someone of Donald Trump’s intellectual stature. /// nCa, 30 January 2026 (to be continued)